"Riding nowhere, spending someone's hard earned pay"

The difficulty of super teams in the NBA, and developing a new framework for how we talk about players.

With Kevin Durant being traded to the Houston Rockets, Bradley Beal being bought out and signing with the Los Angeles Clippers and Damian Lillard being released and returning to the Portland Trail Blazers, we’ve seen a couple of “super teams” dismantled this offseason. We also saw the Durant-Kyrie Irving-James Harden pairing in Brooklyn get dismantled after just a few seasons, the Kyrie-Luka Doncic setup in Dallas get torn down, and the Clippers’ initial attempt with Kawhi Leonard and Paul George fall short. These colossal assemblages of talent have all fallen short of their championship goals and their reigns ended just as speedily as they came into being.

Much of the discussion of these things focus on the players involved and their failings/what they did to precipitate this dismantling. It’s been used as a referendum on the quality and character of some of the players involved—they were surrounded by all this talent and couldn’t get it done, so they must not be all that good.

What this news has made me appreciate is how difficult it is for these teams of this nature to succeed; thus, it was quite remarkable that the 2017-2019 Golden State Warriors, the archetypal super team frequently pointed to as having done something wrong, were able to succeed as much as they did.

What you hear people say is that those Warriors teams—which featured Durant with Stephen Curry, Klay Thompson, and Draymond Green—had such a talent advantage that somehow their accomplishments were invalidated and it all reflects poorly on them. Those championships “don’t count” in some essential way when it comes to evaluating the careers of those players. There’s nothing special or remarkable about what those Warriors teams did because all they did was amass so much talent that their wins were going to happen anyway.

Given how basketball works and the outsized effect that one player can have on a team’s fortune, there’s an assumption that it’s just plug and play. If you acquire a certain level of talent, all you need to do is roll the balls out there and you should win. Recent NBA history tells us, however, that’s not the truth.

Looking at the last five champions, none of them we would define as a “super team,” by which I mean they’re bringing in at least one big piece/superstar and incorporating it. Yes, the 2025 champion Oklahoma City Thunder had a tremendous amount of talent, but that was all “home grown” and the 2024 champion Boston Celtics certainly made moves to improve their team and strengthen their core but nothing at that “super team” level (they didn’t bring in a Durant or LeBron James-level player). The 2020 Los Angles Lakers were probably the last “super team,” but I hesitate to describe them in that way. Yes, there are examples, like the Warriors or the 2011-2014 Miami Heat or the 2008-2010 Boston Celtics, of the “super team” approach working but by and large the “super teams” you see that win are ones that were built from the ground up and not involving the major incorporation of talent from outside the team.

Before our modern era, the example I can clearly identify were the 1983 Philadelphia 76ers and their bringing in of Moses Malone. To me, that was the comp for what the Warriors did with Durant and how well it worked. You had a team that already experienced some success (for the 76ers getting to the Finals, for the Warriors winning in 2015 before the heartbreak in 2016), but they made an addition of an elite player who took them to a different level (for the 76ers it’s their 1983 title, for the Warriors the 2017 and 2018 titles and playing some of the greatest and purest basketball in the history of the sport).

But the bulk of NBA history tells us that this approach just doesn’t work, or doesn’t consistently work. Therefore, when we see the 2017-2019 Warriors, we shouldn’t say they had it too easy. Rather, we should appreciate what they were able to do and the difficulty in it. The 2017 Warriors was the best team in NBA history and their playoff run was one of the great accomplishments in the sport. Durant’s ability to both play within the Warriors system (we’ve seen, in the post-Durant era, what happens when a player can’t play within that Warriors system and how disruptive it can be) and also do everything he does best along with Curry and Thompson and Green’s collective ability to incorporate such a commanding figure on the court seamlessly into everything they wanted to do, that was something that was truly special (and head coach Steve Kerr certainly deserves praise for that too). That it came to easily, too smoothly, to those Warriors teams perhaps doomed the experiment in many viewers’ minds as they bought into that misconception that the assembling of talent was all that needed to be done.

I also think all this points to how inherently flawed the ways we talk about basketball teams and their compositions are. If one player has too much talent around them, their greatness is somehow diminished. Yet, we clearly grasp basketball is a team game and thus one cannot go it alone and needs help. But think about how often you see one player talked about as being “Batman” and the other as “Robin.” Quite a bit actually. There can only be one lead figure and one sidekick. One player is the serious one, the powerful one, and anyone else is just on the side. What people didn’t like about the KD-with-the-Warriors pairing (and the sentiment that likely undid that combination) was how it went against that “Batman and Robin” framework. Who was “Batman,” KD or Steph? Was KD unable to be “Batman” because he came to play with Steph’s team?

That’s how some of the major voices covering the sport talk about inter-team relationships and compositions. And it’s ridiculous.

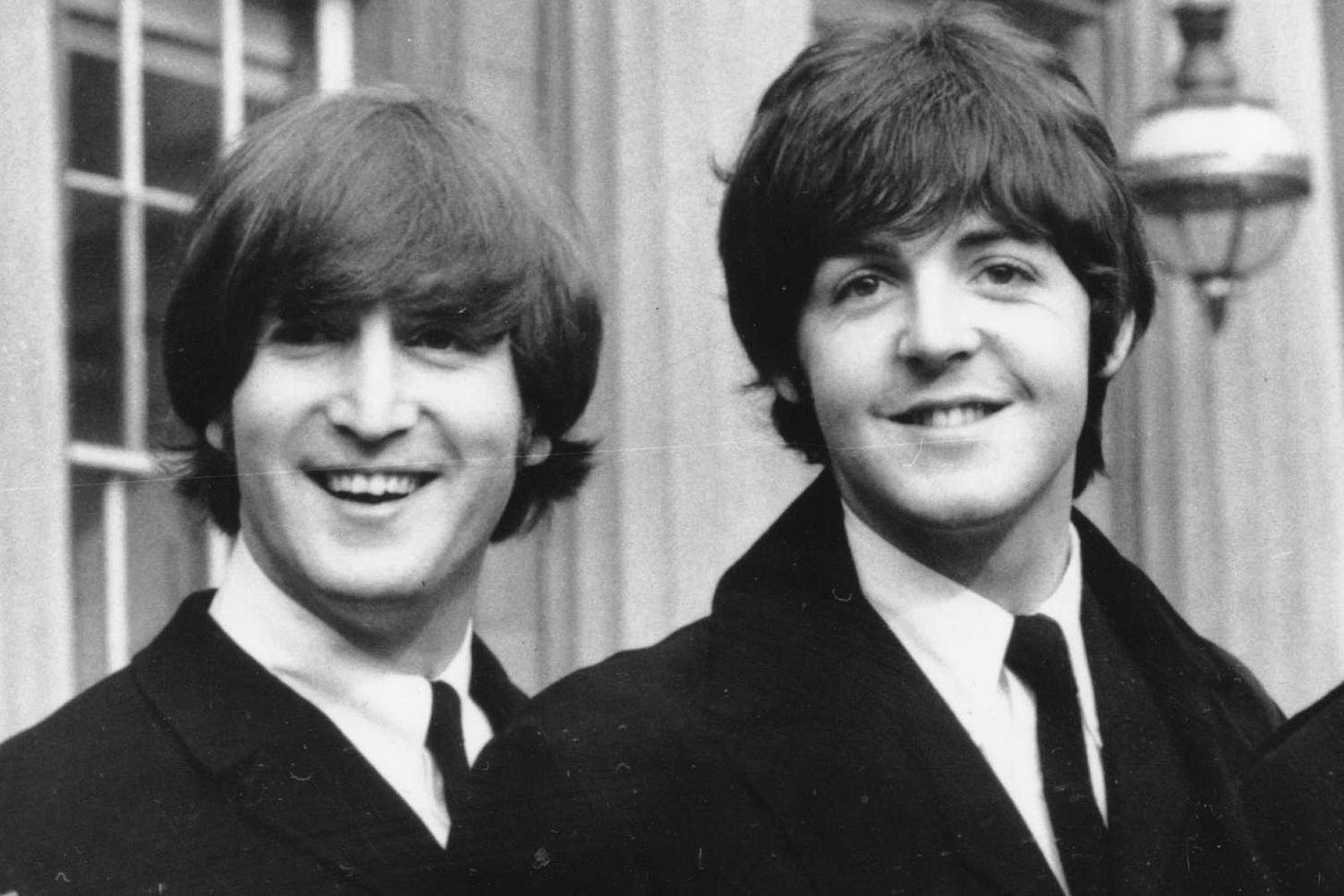

There has to be and, in my search for something more illustrative, my mind turned towards an unlikely source… the Fab Four. No, not the Fab Five of Michigan basketball fame. The Beatles, perhaps the most important and greatest group in 20th century music history. One of the defining aspects of that group was the songwriting relationship/partnership between John Lennon and Paul McCartney. But the composition of songs would be credited to Lennon/McCartney, and one wouldn’t describe Lennon or McCartney as the “lead singer” (and this isn’t even taking into consideration George Harrison and Ringo Starr’s songwriting contributions). They were both distinctive forces with aesthetic preferences and styles, yet they both contributed in a way that was balanced. There were John songs and there were Paul songs, but one wasn’t “better” than the other. Also, what was key to the Beatles wasn’t just them as individuals, but how they all worked and fit in together. There’s a reason we talk about the Beatles so much more than any of their individual solo work.

You think about a song like “A Day In The Life,” one of the Beatles’ greatest, and there’s both the John and Paul parts of the song, but you need both for the song to be as great as it can be. It’s not that one part is “better” than the other, it’s about what the two of them brought to the song and how it works together.

My proposal is that instead of saying about a team that one player is the “Batman” and the other player is “Robin,” we instead talk about who’s Lennon and who’s McCartney. It establishes that players have unique gifts and the things that make them distinct, but they are working within a collaborative medium and the genius comes from the work they do together. For those 2017-19 Warriors, it goes without saying that KD is the Lennon and Steph is the McCartney. I also think this paradigm could work using other bands (you could do it with The Rolling Stones, starting with the Mick Jagger-Keith Richards dynamic). It’s something I’m thinking about exploring—teams and their music group comparisons.

But rather than looking to a metaphor that’s so hierarchical (Batman is clearly above Robin), we should use something that’s much. more collaborative as basketball is such a collaborative sport. For a band to be great, it needs the right combination of members (the Beatles couldn’t become THE BEATLES until it was John, Paul, George, and Ringo). Part of what made that group great was Lennon and McCartney working together on songs. We don’t talk about who was the “Batman” and “Robin” of the Beatles or The Rolling Stones or any other great musical group. Yes, we have our preferences (honestly, as time has gone on, I’ve become more of a George guy when it comes to my favorite Beatle) but we recognize a group is a collaboration and it’s about what all the members of the group are bringing and contributing to the whole. We should talk about basketball using that mindset, and, honestly, it’s staggering we aren’t already.