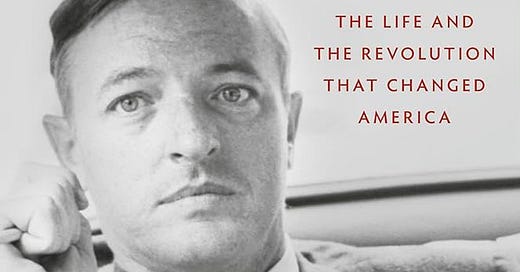

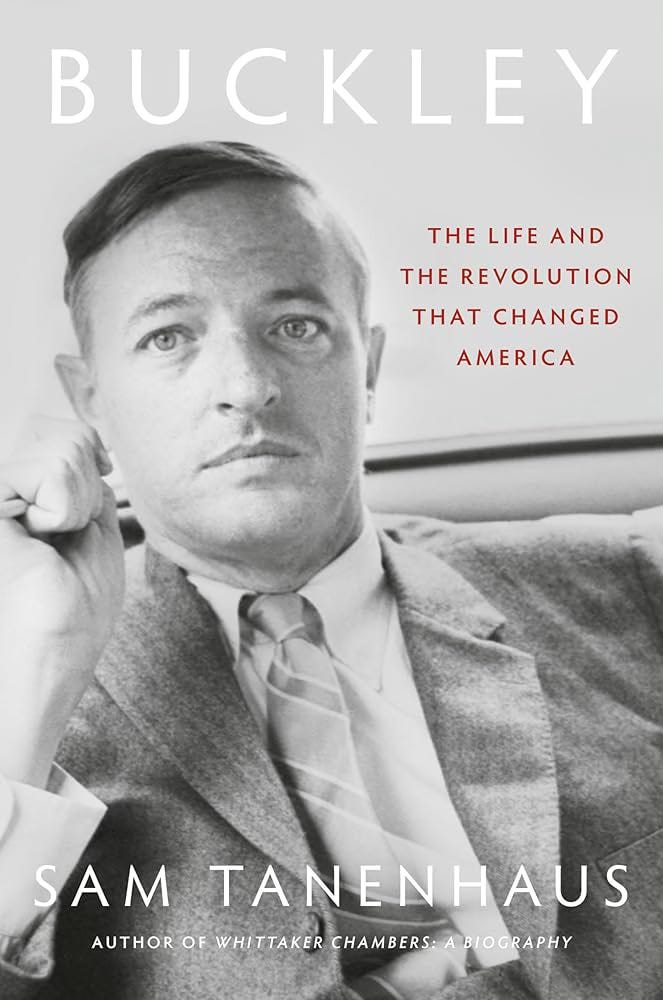

Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America

My thoughts on Sam Tanenhaus' excellent biography on the National Review founder who shaped much of American politics in the mid-to-late twentieth century.

I feel confident in saying that Sam Tanenhaus’ Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America is one of the most hotly anticipated biographies by those of us with an interest in American history and politics. Tanenhaus, author of the Whitaker Chambers biography that was a finalist for the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize, was picked by William F. Buckley Jr. himself to write his biography and spent the subsequent years and shifts in America writing this expansive work on the life of Buckley.

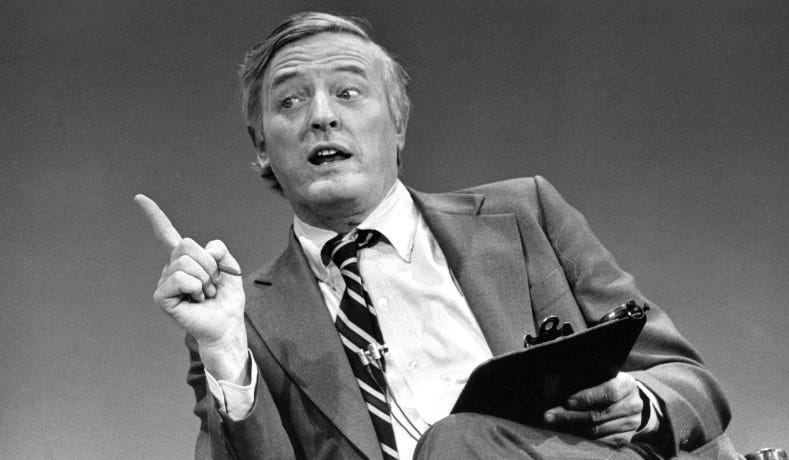

Tanenhaus gives us the life of the man who founded and edited National Review, created an d hosted Firing Line, wrote God and the Man at Yale amongst other books, and re-shaped American politics through the creation of a true conservative Republican Party. Were one to generate a list of those who’ve had the greatest impact on American politics but not a president or a senator, you’d have to include Buckley. Tanenhaus takes us through the early years of Buckley’s life, through his time at Yale, his founding of that seminal publication, his connections with such major figures as Joe McCarthy and Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, his feud with Gore Vidal, and all the other ups and downs of his life. You grasp how the story of the mid-to-late twentieth century in American politics could not be told without a consideration of Buckley. It is extensively researched, well-written and engaging, holding your attention on this one figure over the course of a voluminous tome.

What was perhaps most amazing and speaks to the high quality of the biography and its author is that Tanenhaus was able to take a figure in Buckley and paint a picture of him that is remarkably… fair. There have been books by conservative commentators and writers who have written about Buckley and produced what amounts to hagiography. I’m sure there’s ample pieces out there by liberal/left leaning writers that take Buckley to was was a force behind all that is wrong in the country. Thankfully, Tanenhaus takes neither of these approaches. I want to understand who this man was, both good and bad, and that’s what Tanenhaus presents.

As I was reading, there was much I found that was charming or interesting or relatable about Buckley (someone who possessed a different ideology and worldview than me). Yet, I was also clear on the ways in which there were parts of Buckley’s life and the stances he took that were not in keeping with what I (or someone like me) would value. I certainly don’t pretend that I agree with Buckley on many things, but he’s someone who I’ve always appreciated and found fascinating (not just because I appreciate the way he dressed, though that was part of it I will not lie). Given the reader that sense of your main subject, particularly when they were as polemical as Buckley is, really reflects a mastery of the biographer’s craft and we must again single out Tanenhaus for praise on that count.

Another thing attesting to the quality of Tanenhaus’ biography is that I finished reading this massive, thousand-plus page book and found myself wanting… more, quite a bit more actually. There are two areas (one of which is perhaps particular to me) that I would’ve liked to have seen more time given to. One area is that of Buckley as the literary man. Tanenhaus references Buckley’s friendship and appreciation for Norman Mailer and makes an interesting connection to Fitzgerald’s creation of Jay Gatsby at the end of the book, but other than that the aspect of Buckley and the literary world of midcentury America isn’t really explored. Buckley had many of our great writers as guests on Firing Line—not surprisingly, I think Kerouac’s appearance on the show (admittedly, one in which Kerouac isn’t at his best) is fascinating and reveals something about Kerouac (the tradition he possessed and understood even as he was such a revolutionary figure).

But the origin of National Review—as a response to the “little” magazines of The Nation and the New Republic—points to the ways in which it brushed up with the literary culture of the mid-twentieth century in America. I also think the role Russell Kirk, a scholar of T.S. Eliot, played in the creation and development of National Review highlights this too. Perhaps Buckley and the literary world is something I can elaborate on given that’s an interest of mine, but I wanted to see Tanenhaus touch on it just a bit more.

I also thought that the final decades of Buckley’s life, the years following Reagan’s election to the presidency and that cementing of Buckley’s conservative thought as such a power player in America, get a bit glossed over. I can see that choice being made from a thematic perspective; namely, that Reagan’s win both signaled an ascension but also that it was the end of something. Perhaps that’s why much of Buckley’s life following Reagan’s 1980 win is glossed over and sped past. I would’ve enjoyed seeing that time examined a bit further, but I also understand that one can ‘t cover everything and Tanenhaus had to give the most time and weight to what he’s identified as the most important stretch in terms of Buckley’s historical influence.

In the moment we’re in now, I feel like there’s a lot of discussion regarding “what would [this person] think of politics as they are now?” I don’t know whether Buckley would be a Bulwark writer Republican who might turn away from the institutional party itself. The fact that Buckley lent his support to Joe McCarthy tells me he would be willing to put in his lot with those who might seem vulgar if it meant work being done that he valued. I do think that the level of discourse would be something that appalled him—look at the guests he had on Firing Line! He was more than comfortable engaging with those he disagreed with in a respectful way (while never pulling any punches nor hiding what he thought). I’m honestly not interested in such questions and don’t think they’re particularly interesting. Sam Tanenhaus’ biography Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America solidified the sense I had of Buckley as a figure and commentator. While I will not pretend that the presence of Buckley would solve everything that ails our political discourse these days, I do think things would be a bit more interesting, thoughtful, and lively if he were with us today.